2019 Reinhart Butter Design Affair Produces New Concepts for a Happier, Healthier Campus Culture

Is psychological well-being really a problem on college campuses?

The Department of Design takes the mental health and happiness of students and faculty very seriously. In January 2016, USA Today presented an alarming set of statistics about the mental health of students on college campuses in America. Half of all students at universities express feelings of hopelessness at some point, they reported, and two-thirds of students who struggle with mental health challenges do not seek help. Suicide was the second most common cause of death among persons aged 15-34 in 2016, according to the Center for Disease Control, and one in twelve college students makes a suicide plan at some time during their time as a university student, according to the newspaper.[1]

Many students in universities already have mental health problems when they arrive on campuses. An international 2018 World Health Organization survey of 14,000 first year students in colleges found that one third of them dealt with mental health disorders in the years that preceded their college enrollment.[2]There is no reason to imagine that students at Ohio State do not fit the profile of these international averages. In fact, our university increased the number of mental health clinicians on campus by twelve in 2016-17. It now provides one therapist for every 1,500 students on campus… a number that exceeds the national average, but that is only the recommended minimum.

Other efforts that are in the works at Ohio State include the creation of an app that makes it easier for students to schedule appointments with clinicians and to contact the mental health clinic in cases of emergency. The app also teaches about stress management by providing breathing exercises and other information about mental health management best practices. Even with these treatment options and support system in place, the mental health of Buckeyes continues to be a topic of concern on campus.

Of course, stress and anxiety on campuses is not restricted to students. The process for faculty members to secure tenure can be riddled with pressure, as is the on-going need to excel in research and teaching. When even one faculty member in a group is dysfunctional for reasons related to mental health, an entire departmental culture can be derailed. Chronic reductions to workforces can lead employees to experience increasing tension and stress as their responsibilities swell to overwhelming. And while universities like Ohio State have expanded the attention they pay to the mental health of faculty and staff, those resources are still often insufficient or hard to access.

Re-framing the problem

The timeliness and seriousness of these concerns formed the subject of the 2019 Reinhart Butter Design Affair. On April 5thand 6th, an interdisciplinary gathering of designers, mental health experts, and concerned members of the campus and Columbus communities who came together to use design thinking to speculate about what a Happy Campusmight look like. With input and guidance from Dr. Claudia Trudel-Fitzgerald of Harvard University’s Lee Kum Sheung Center for Health and Happiness and expert workshop facilitation by our own Dr. Liz Sanders, we spent two days re-framing problems and generating design concepts that could potentially transform the culture of universities across the country, with a specific applicability to large public institutions like Ohio State.

The event kicked off with a series of quick pecha kuchapresentations to provide a framework for understanding what happiness is and how various fields from philosophy to psychology approach it. In a series of rapid-fire six minute and forty second-long presentations, campus organizations that promote mental health and happiness-related programming also helped broaden our understanding of the state of our campus today.

Dr. Trudel-Fitzgerald’s keynote presentation provided evidence that positive mental health is linked to physical health, but not in the same way for all kinds of people. Her perspective on long-term studies that tied psychological well-being to feelings of life satisfaction and purpose served as a valuable reminder of just how complicated the many dimensions of happiness are. She also explained how persons of differing ages, genders, and races express their connection to happiness through perceptions of optimism, life satisfaction and positive affect in their lives.

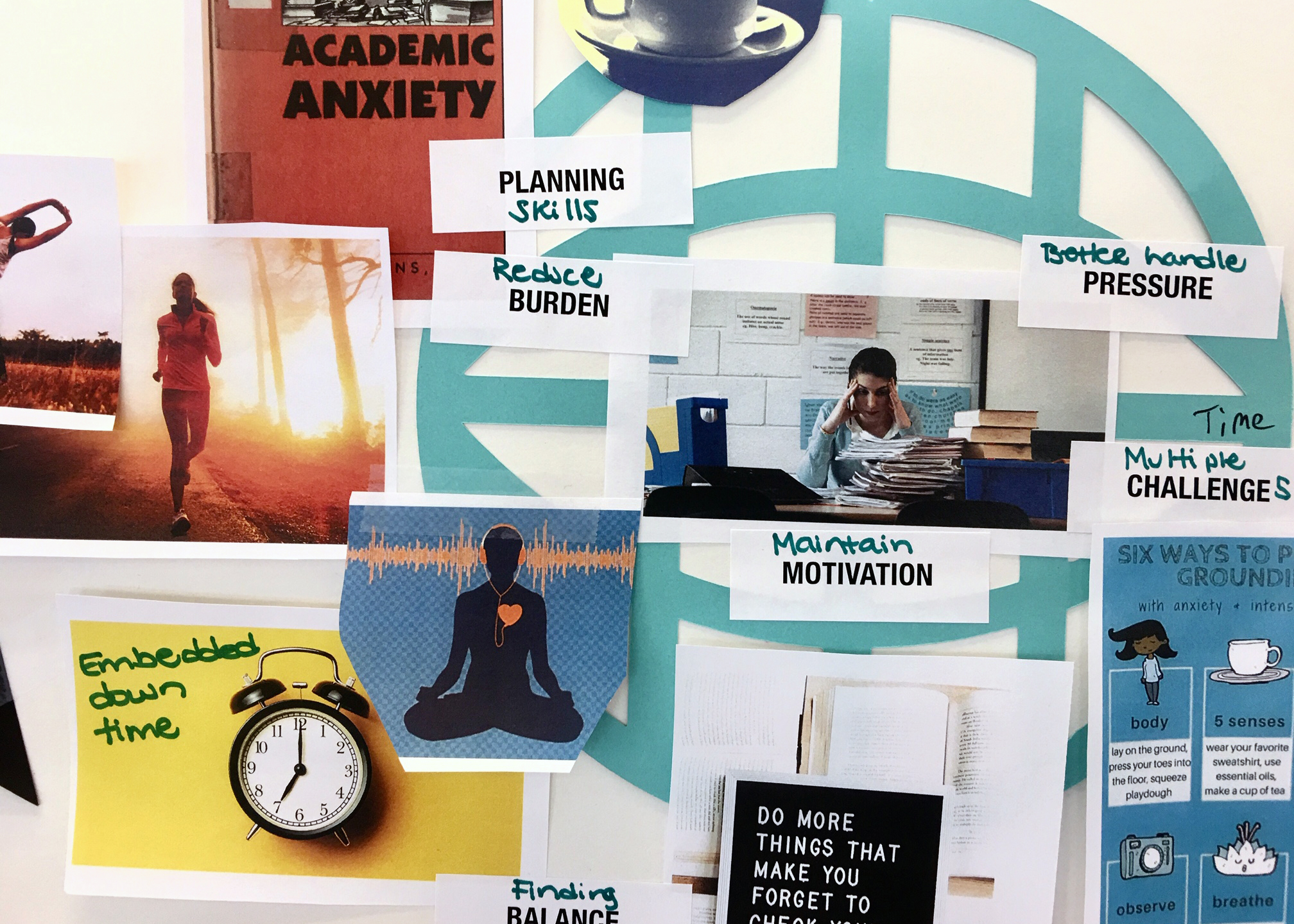

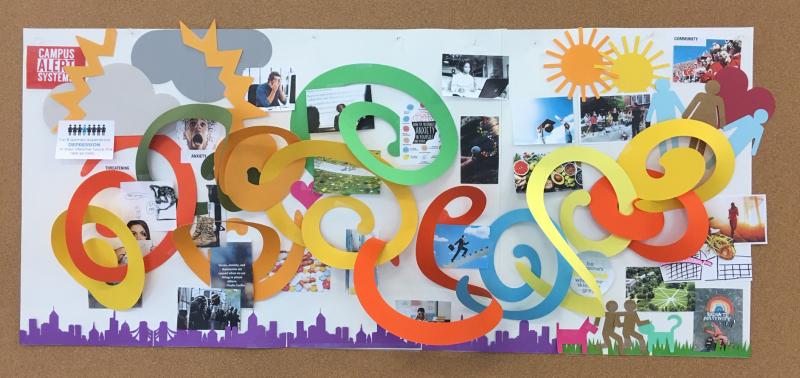

Participants in the first day’s workshop explored how to define, express, and portray conditions found on campus today as a means of creating a shared understanding of the problem as we defined it. By discovering where and how the campus is already happy, as well as where the most significant challenges to happiness occur, workshop participants laid the ground work for envisioning the happy campus of the future using visual tools and collaborative creation techniques.

So what came of this initial round of design-focused speculations? Our analysis of current initiatives that work and areas that need improvement revealed that the vastness of our amazingly diverse and complex university may not actually be a source of happiness for persons associated with it directly. We concluded that it is critical to look for better ways to break down the immense scale of the campus to ensure that students, faculty, and staff are empowered to live their most satisfied lives here.

So what might the happy campus look like?

First, we need to do more to help big universities feel smaller. Since passive learning and large-scale lectures rarely produce effective learning experiences, we encourage the radical move of shifting all courses with enrollments larger than 30 to on-line delivery models. That could mean that all face-to-face learning offers the advantage of facilitating personal connections among students and their instructors. Also, by decreasing the demand for large-scale learning environments, new spaces for focusing on wellness could be created. Former classrooms and lecture halls that are already embedded throughout the landscape of campus could host art installations, musical or theatrical performance spaces, fitness-oriented activity space, areas for play and gaming, or quiet zones for mediation and contemplation. Proactive wellness and happiness become literal and physical priorities over passive learning and anonymous student experiences.

A second speculative idea is to isolate a predictable block of unscheduled time each day across the entire campus—not for pop-up impromptu meetings but for mandated quiet time to be used for individual productivity, introspection, or even a nap! Relief from the feeling that every minute of every day must be scheduled and productive has proven health benefits beyond people’s perceived states of happiness.

One of the more significant causes of stress on college campuses is the perception that true success can only be achieved by getting things right the first time—the fear that poor grades will derail the long-held dream of a career or that a lull in productivity will jeopardize continued employment can be paralyzing. So what would be the cost of becoming a “university of second chances” with majors that reward exploration and the failure that goes hand-in-hand from risk-taking and boundary pushing in ways that are linked to satisfaction and well-being? What if mechanisms to re-set or re-do are built into the way we mentor and support the future leaders in our fields? Might simply knowing that second chances are available increase the happiness that should permeate academic life?

Among the other ideas worth developing is the notion of making better use of resource finding aids and pathways in the happy campus. Universities as large as Ohio State need better tools to help students, staff, and faculty navigate what is an admittedly dense and often complicated system of sometimes redundant programs, organizations, or activities that are intended to support psychological well-being. Making strong meaningful connections is an important attribute of happiness, and more could be done to ensure that our networks work together effectively.

Likewise, student are stressed about the cost of their education, the time required to complete majors, and they are challenged to find the major quickly that will support their career goals. This pressure could be mediated with more effective “roadmaps” that demonstrate the many potential paths to most future goals. With sometimes radical career changes becoming the norm for many professionals, could starting from the perspective that many paths lead to careers also encourage competing programs to behave more cooperatively, thereby enhancing happiness among new allies? Could students who struggle to find the “perfect” major and finish in four years find reassurance if presented with multiple choices that have varying degrees of investment required?

The ability to be part of a community; to get help when you need it; and to create a way to see a healthy and productive future for ourselves and for the world around us… these are some of the building blocks for sustaining happiness in people. Why not design a university that has these features and more? With space and products that encourage wellness and communication systems that decode and connect people to people and people to resources, our universities could transform themselves and model happiness as a fundamental feature of learning and discovery. With good design, the happy campus may not be so far away, after all.

[1]USA Today, January 30, 2016. https://www.usatoday.com/story/college/2016/01/30/mental-health-on-college-campuses-a-look-at-the-numbers/37410977/(accessed 4/7/19).